Notes

Overcoming RF Design Challenges: Strategies and Solutions

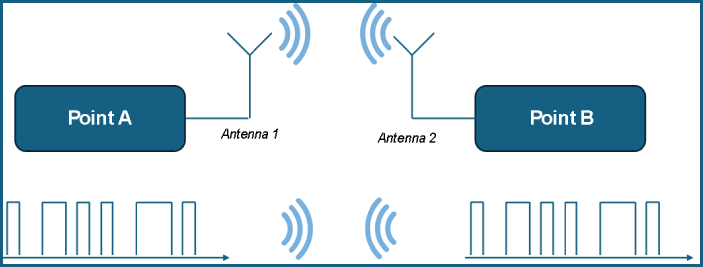

Radio Frequency (RF) systems are at the heart of all wireless communication technologies, enabling the seamless transmission and reception of data over the air. These systems are composed of three essential components: a transmitter, a receiver, and an antenna. The transmitter converts digital signals into high-frequency analog signals and radiates them into space. The receiver captures these signals—often weakened and distorted—and restores them to a usable form. Meanwhile, the antenna serves as the interface between electrical and electromagnetic energy, playing a crucial role in both transmission and reception. In this article, we explore the building blocks, performance metrics, and design considerations of RF systems, from signal processing fundamentals to real-world optimization techniques that enhance range, efficiency, and overall communication reliability.

I. Principles of an RF system

An RF system is responsible for the transmission and reception of a wireless message between point A and point B. It consists of:

The transmitter, which is used to

Generate an analog baseband signal from a digital bit sequence.

Modulate this analog signal and convert it to RF frequency.

Amplify, match, and filter this signal to transmit this signal over the air.

The receiver, which is used to

Amplify the (weak) received signal.

Convert it back to the baseband signal.

A receiver has the opposite function compared to a transmitter

The antenna, which is used to

Convert the electrical energy from the transmitter into electromagnetic energy with maximum efficiency.

Convert the electromagnetic energy into electrical energy on the receiver side with maximum efficiency.

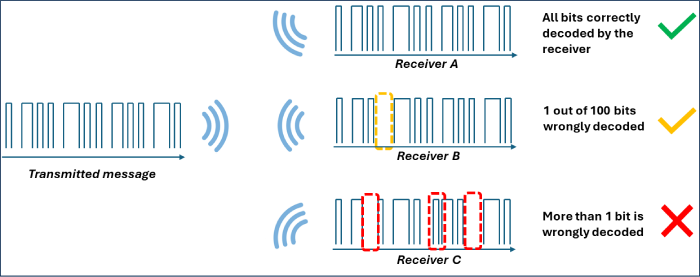

We can say that this RF system is effective when the decoded message from the receiver is on par with the transmitted one, allowing a certain level of possible errors in certain applications (for example, 1 wrong bit or packed decoded over 100 received).

Transmitter

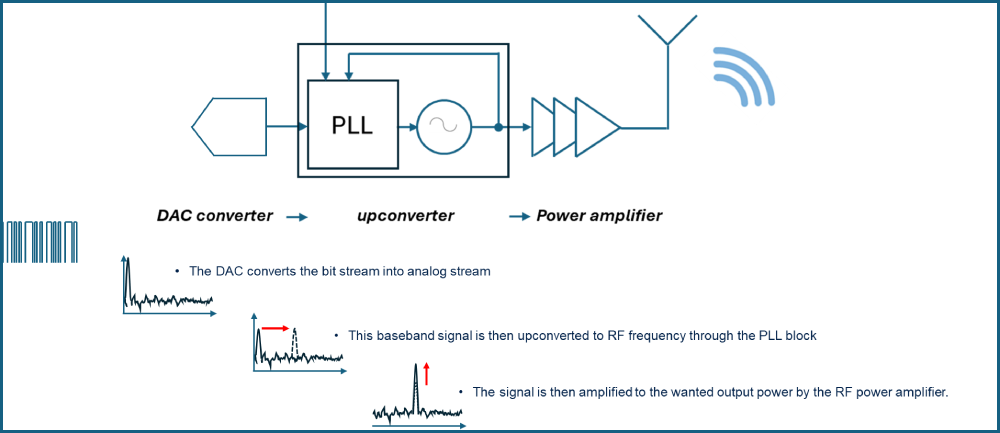

The transmitter aims at upconverting to RF frequencies and at a sufficiently strong level, a digital baseband input signal.

To do so, the following basic architecture can be used.

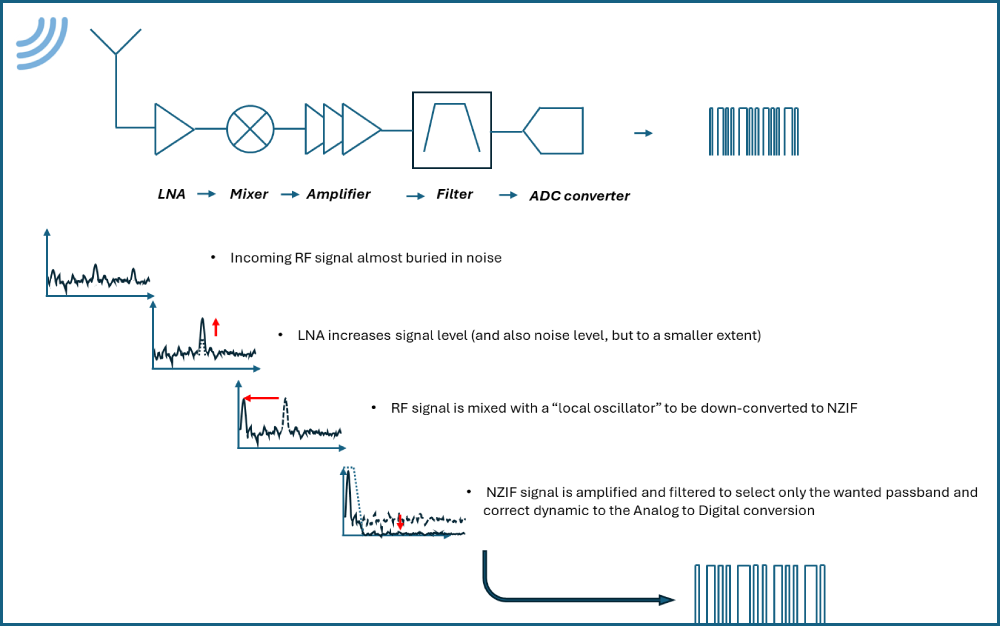

Receiver

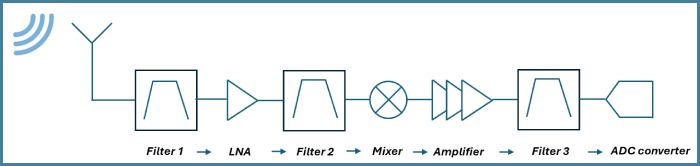

Received electromagnetic signals are often very weak and can be perturbed by interferers all along their path, either on the same frequency or on a nearby frequency.

It is then crucial for the receiver to be able to extract from this overall noise the wanted signal in the best possible conditions.

A bulletproof but historical receiver principle looks like this:

Filters aim at cleaning the signal from more or less nearby interferers.

LNA (Low Noise Amplifier) aims, thanks to their gain and noise figure, to provide a sufficiently strong and above-noise signal to be decoded.

Mixer aims at down converting the radiofrequency signal to a lower frequency by mixing the incoming RF signal with a steady carrier.

This could be done at baseband or at a low intermediate frequency (Near-Zero Intermediate Frequency = NZIF)

ADC converter to move this still analog signal into a train of digital bits.

In ST platforms, architecture is simpler, but the same functions can be seen.

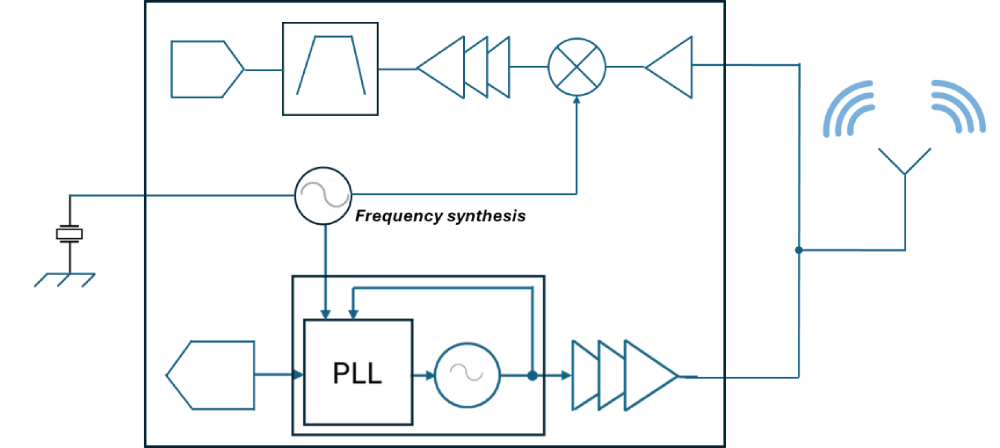

Transceivers

The word transceiver is the contraction of TRANSmitter and reCEIVER. This is a single component integrated in the same package for both functions.

Note the common block called “frequency synthesis”.

This is the block that generates the local oscillator used in both up and down frequency conversion.

It is based on an external reference clock (either a simple Xtal XO, or a more complex Temperature Controlled XO) whose accuracy will determine the frequency accuracy of RF signals of the transceiver.

Antenna

When designing RF systems, we need to translate the electrical energy into an electromagnetic one, so that it can propagate, generally through the air.

The fundamental element which does this conversion is the antenna and with transceiver solutions, the same antenna is used for both transmission and reception in most of our applications. Its role is crucial to ensure optimum radiated performances.

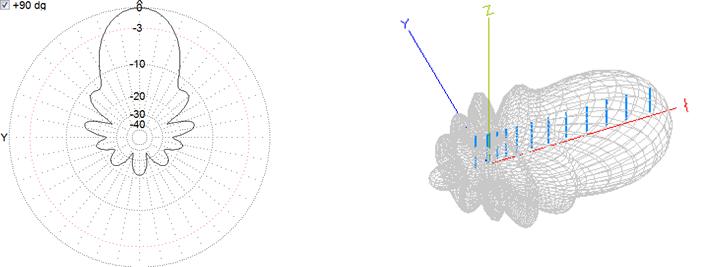

Antennas are generally characterized by their:

Resonance frequency / Characteristic impedance/bandwidth

Ideally, the antenna, by design, should be resonating (aka showing a minimum loss) at the RF frequency for which it has been designed.

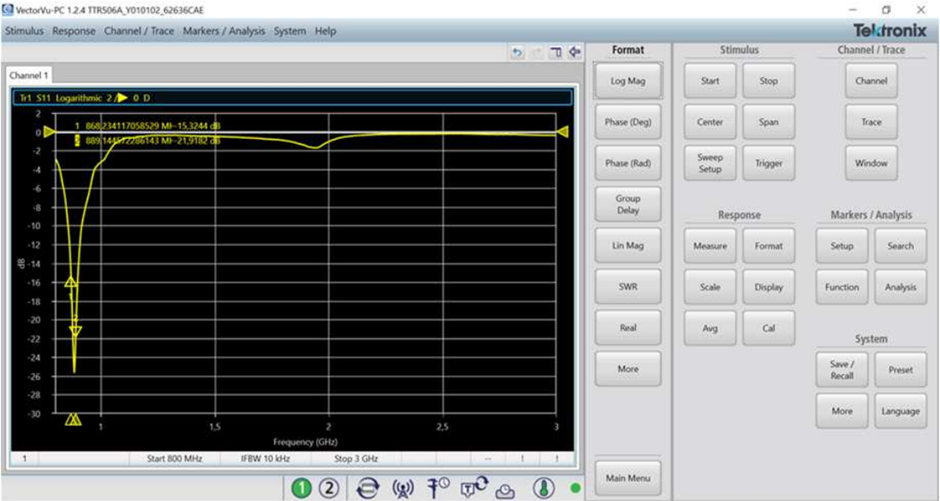

It has a certain bandwidth, that can be defined as the frequency band where those losses are minimized. The S11 parameter is then used to measure the correct return loss, that is to say, to check that most of the injected signal is effectively radiated.

Most of the antennas are not 50-Ohms by design and therefore, a matching circuitry must be used that can also adjust both resonance frequency AND impedance with the transceiver RF front-end 50-Ohms impedance.

Note that impedance matching is not enough to judge the quality of the antenna.

Directivity, efficiency and gain

Antenna directivity is the ability to focus energy in a particular direction when transmitting or to receive energy better from a particular direction when receiving

Antenna Efficiency (Eantenna) is the amount of energy radiated, compared to the amount of energy at the antenna feed-point.

Antenna Gain (G) is the product Eantenna *D and is generally given in reference to a standard antenna (for instance, an isotropic antenna).

II. Some RF Definitions and Units

a. The dBm

In RF world, the logarithmic scale is used. But a decibel (dB) being a relative and not an absolute value, the “dBm” has been created to refer to a reference power (“m” standing for mW) and to give an absolute value.

Power dBm = 10*log(Power in mW / 1mW)

Using such a logarithmic scale is very intuitive since it simplifies the different calculations: Gain and losses can then simply be added or subtracted for a reference power expressed in dBm.

“I have a 16dBm output power at antenna input, but my antenna has a loss of 3dB, so my radiated power is 16-3 = 13 dBm.”

b. Receiver sensitivity and selectivity

Sensitivity: This is the minimum input power on the receiver side at which data are correctly decoded.

To determine this sensitivity, we decrease the power at receiver’s input, till reaching a certain number of errors, either this is Bit Error Rate or Packet Error Rate.

ETSI standard, for instance, specifies the sensitivity threshold to be at 0.1% BER.

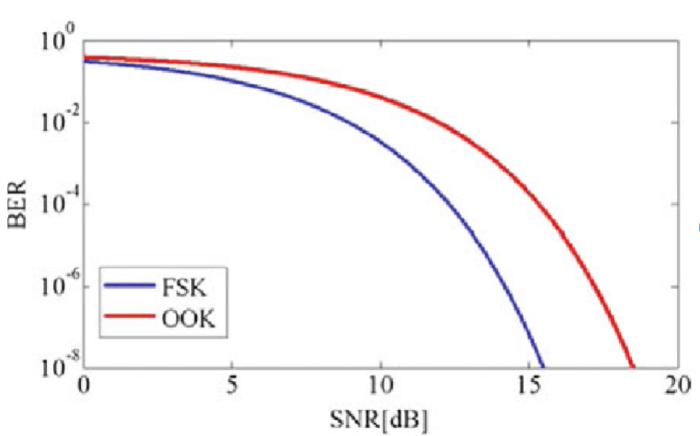

Note that the sensitivity cannot be at the same level as the noise floor: The wanted signal must be at a certain level above the noise level to be correctly demodulated. This is called Signal over Noise Ratio (SNR) and its minimum value depends on the modulation used.

Typical SNR for a 1% BER is:

For FSK modulation, around 9 dB

For OOK modulation, around 12 dB

Selectivity: Same definition as sensitivity, but this time in presence of strong near-by or far-by interferers. This aims at testing the robustness of the receiver in a harsh environment.

Some receiver categories are defined by ETSI or Wireless-MBUS standard since this criterion may be required for sensitive applications like medical ones.

When interferers are located on the adjacent or alternate channel, so very near the wanted frequency, this is called Adjacent Channel selectivity.

When they are located outside of the receiver bandwidth, this is called out-of-band blocking.

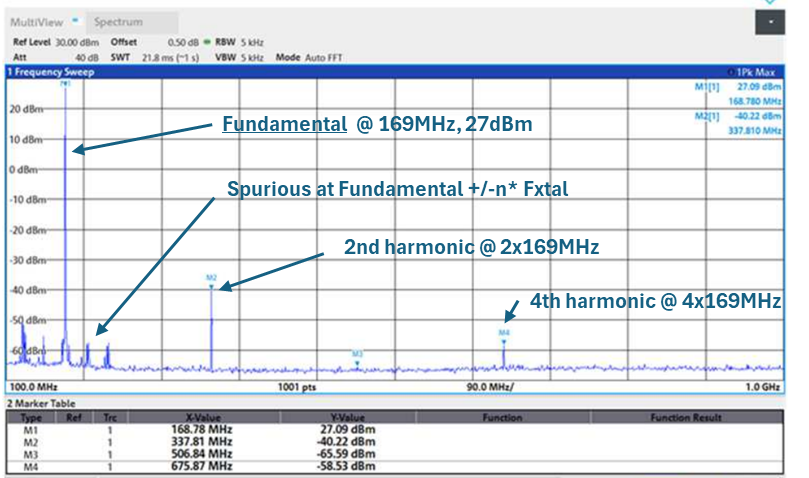

c. Transmitter output power, harmonics

2 main performances can characterize a transmitter.

Of course, its output power on the fundamental frequency

But also, the generated unwanted spurious signals it can create, such as

Intermodulation products (possible recombinations of frequencies within the chipset with Xtal, VCO, etc.)

Harmonics (generated at n* the fundamental frequency), which are a particular case of spurious.

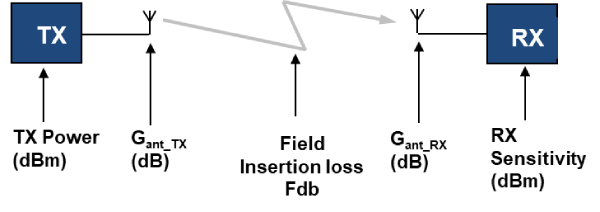

d. RF link budget

As we are talking about RF communication, one important criterion is the distance that can be covered.

This distance depends on a few parameters.

Output power of the transmitter (Ptx)

Input power at received input (Prx)

Receiver sensitivity (S)

Transmitter antenna gain (Gtx)

Receiver antenna gain (Grx)

Field insertion loss (FSPL Free Space Path Loss)

RF communication will be possible if the power received at the receiver input is equal to or stronger than its sensitivity level. This can be put into the following equation:

(Eq1) Prx = Ptx+Gtx-FSPL+Grx > S

The RF link budget is then defined as:

(Eq2) RF link budget = Ptx – S + Grx + Gtx

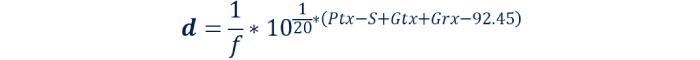

In addition, the FSPL (Free Space Path Loss) can be approximated as:

(Eq 3) FSPL = 20*log(d) + 20log(f) + 92.45

With D = in km / F in GHz

So mixing Eq1 and Eq3, we can approximate the theoretical maximum distance for an RF link in free space.

Example

S = -110 dBm / Ptx = +16dBm / Gtx = Grx = 0 dB / F = 0.868GHz ==> D = 54 km!

Those free Space loss conditions never occur in real life, and the real RF range will be lower. We can distinguish 3 main propagation conditions:

Line of Sight Range: Best possible outdoor conditions with no obstacles

Urban range: Buildings and obstacles present and create some multipath propagation/absorption factors.

Indoor range: Walls, concrete, doors, and closeby metallic objects affect the range.

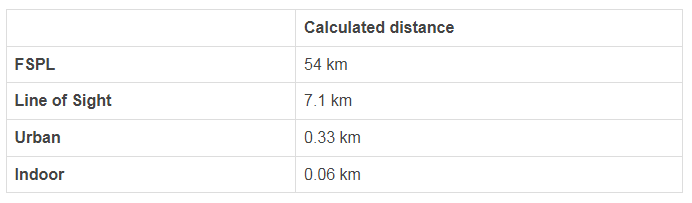

We can find some more or less realistic evaluation tools on the net for each propagation path. Using the same data, we obtain the following results as an indication.

Why is it important to optimize all the power transfers (output power and sensitivity) and the antenna gains to maximize the distance achieved?

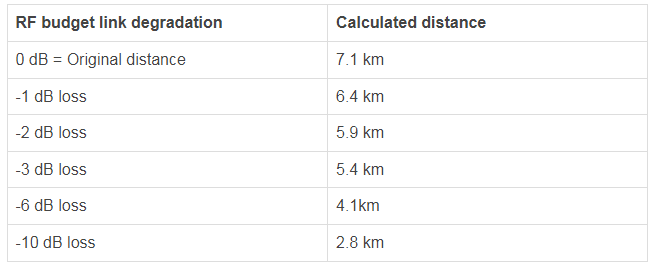

Let’s consider a “line of sight” propagation and see how the RF range decreases if we degrade the RF link budget.

It is very difficult to improve the output power or the sensitivity by 1 or 2 dBs. But it is very easy to lose 3-4 or even more when choosing a bad antenna with poor efficiency.

This is why we must ensure all the power transfers are done optimally, and this can be done through correct matching and filtering of the RF components.

e. Impedance, matching and filtering.

An important criterion in RF consists of adapting the impedance between RF blocks to

Ensure the maximum transfer of energy (“matching” impedance such as antenna matching and Power Amplifier matching)

Filter some frequencies (low-pass, high-pass, bandpass filters) to let or reject such or such frequency bands.

Often, a compromise must be made between RF output power, spurious suppression, and sensitivity

To do this, we generally use discrete components such as RF coils (in the nH range) and capacitors (in the pF range).

Such components have some tolerances (i.e., possible dispersion across their nominal value) and quality factors (representing their intrinsic losses).

For instance, wire wound coils have fewer losses than multilayer ones but are more expensive.

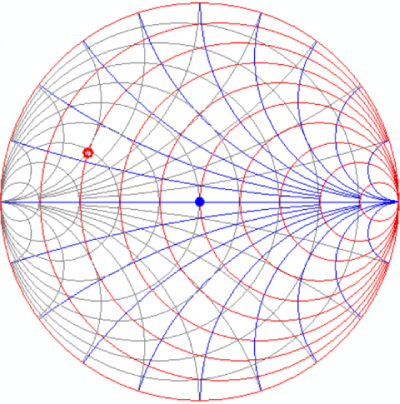

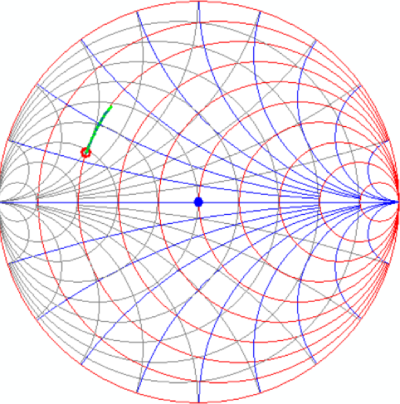

Some free tools exist to indicate which component to use to adapt a “non-50 Ohms impedance” to a 50 Ohm load, using the Smith chart method

Example :

Let’s consider an antenna that has a complex 12.5+j10 impedance at the desired resonance frequency

Step 1: Use a serial 2nH coil, impedance goes to 13 + j20

Step 1: Use a serial 2nH coil, impedance goes to 13 + j20

Step 2: Use a shunt 6.2 pF capacitor: Impedance is now 50 + j0.5

Step 2: Use a shunt 6.2 pF capacitor: Impedance is now 50 + j0.5

Those tools are purely indicative of the topology to be used, but they represent a good starting point. Values may need to be slightly tuned to cope with PCB/component/GND influence on real form-factor PCB.

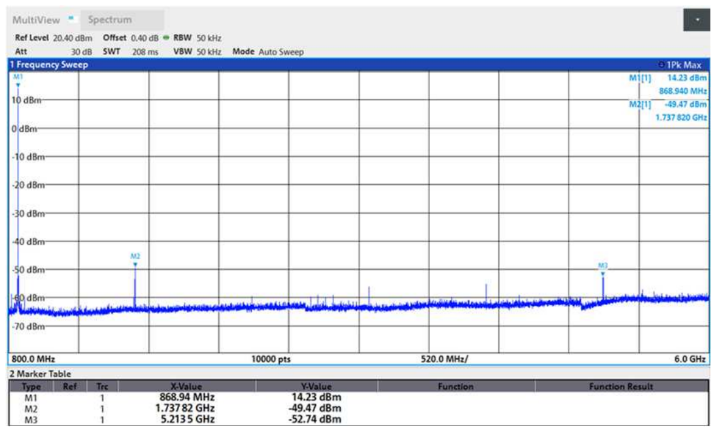

Example 1: Sub-GHz BOM Optimization

The customer is willing to reduce as much as possible TX components while maintaining a sufficient margin for harmonic rejection, in order to optimize the overall Bill of Material.

Starting point:

With the customer’s original PCB, more than 20 dB of margin for the 2nd harmonic are achieved, using wire-wound RF coils.

Investigation track:

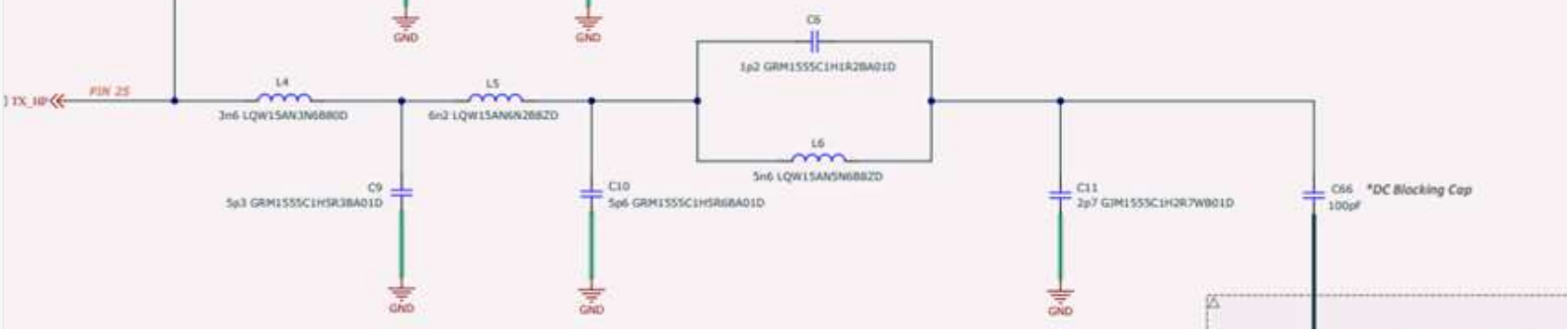

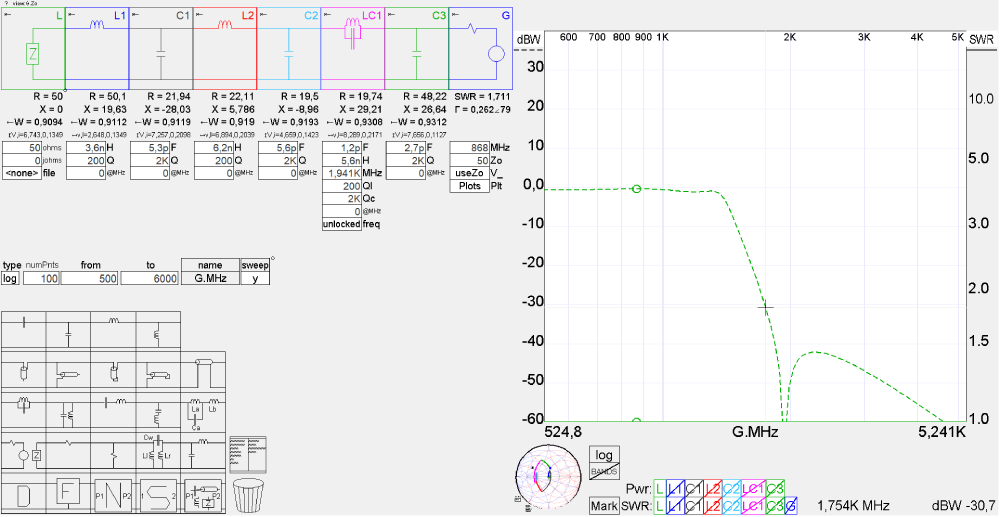

This margin is obtained using 2x series L-C filter, followed by an LC notch, and terminated by a shunt capacitor which removes higher frequencies. There are some freedoms to decrease the number of filtering cells to see what that brings in terms of rejection.

Work done:

Simulating this circuitry gives us the following response:

For H2, this circuitry brings slightly more than 30dB of rejection.

This huge margin allows us

to remove one “LC” series filter

to choose low-Q RF coils (multilayer, so cheaper technology)

to re-tune the component values.

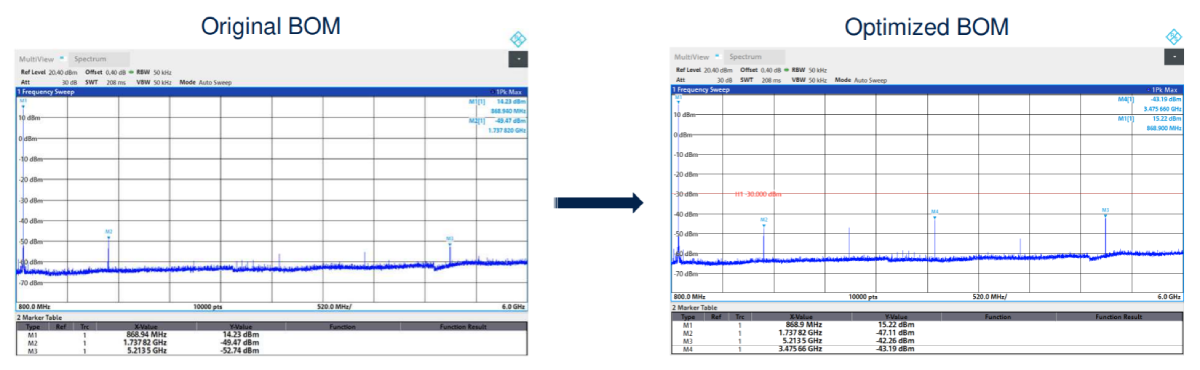

Results:

Of course, removing one “LC” low-pass filter cell will increase the level of the harmonics, but

We are still >12 dB above the RF standard spec; this is fully acceptable.

One less series LC cell also means smaller insertion losses.

About 1 dB of additional output power has been measured.

Example 2: BLE Current Consumption Optimization

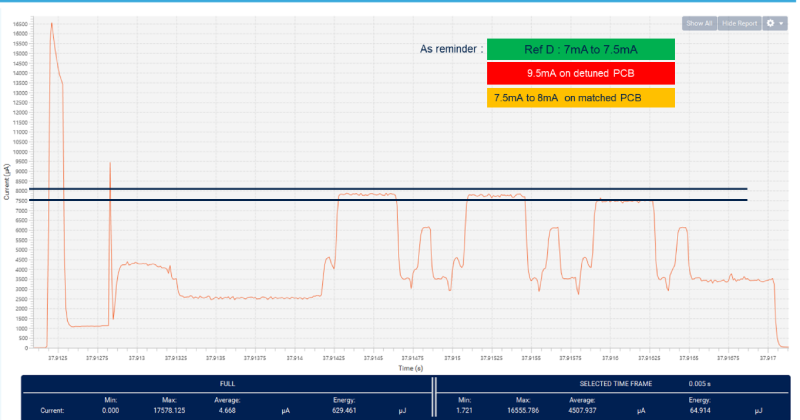

The customer is measuring high current consumption in radiated mode and would like to extend his battery's lifetime by decreasing it.

Starting point:

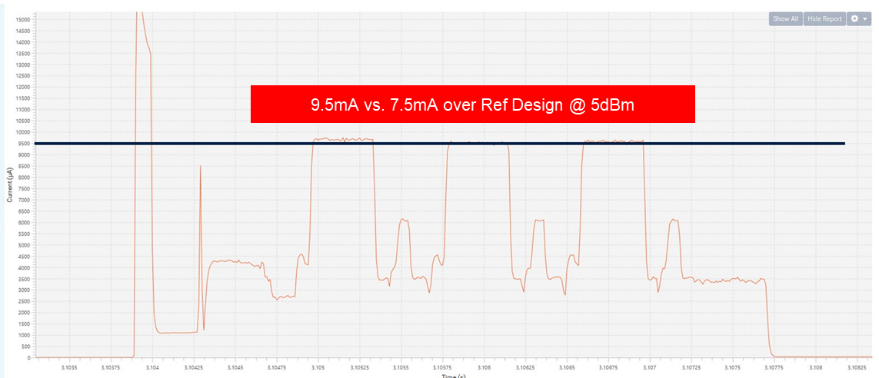

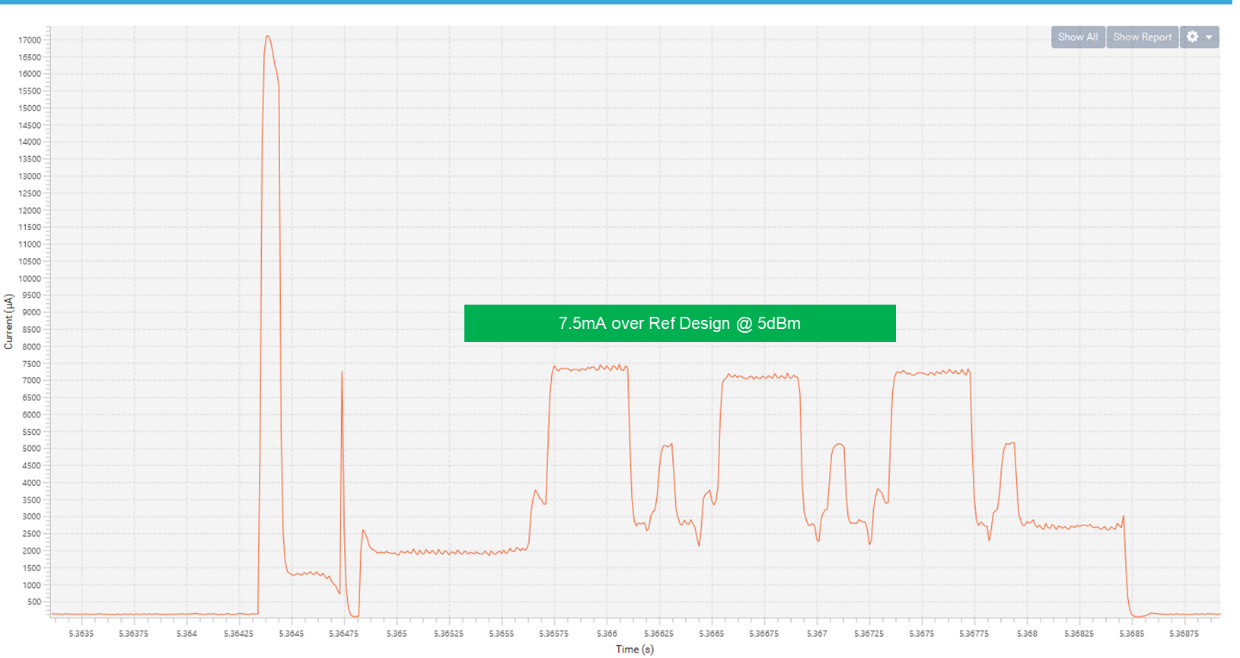

Up to 9.5 mA current is measured during TX bursts, which is higher than on ST reference designs.

ST reference design: around 7.5 mA during the same active phases.

There is a big current consumption difference between both PCBs (about 25%)

Investigation track:

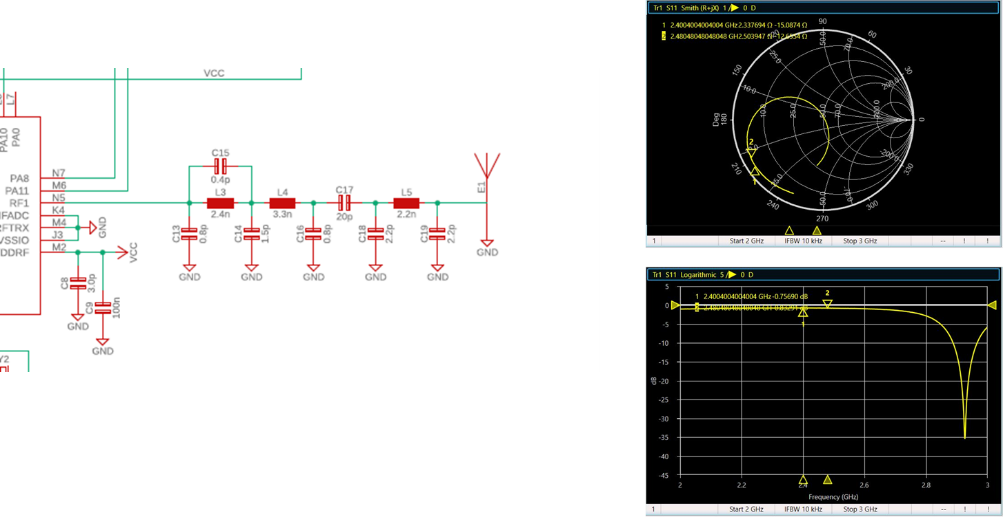

investigations were logically made around the antenna-matching

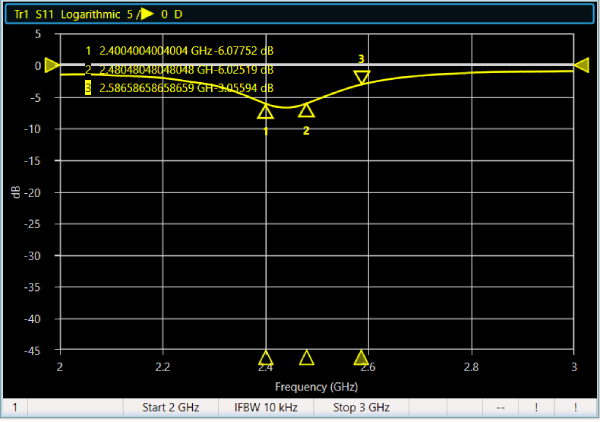

The S11 parameter was measured at antenna input, including its original matching network (L5/C19), but excluding the rest of the components of the RF filter.

Results revealed that the antenna is far from being resonant on the wanted BLE frequency bands and it must be re-tuned to minimize losses in the wanted bandwidth.

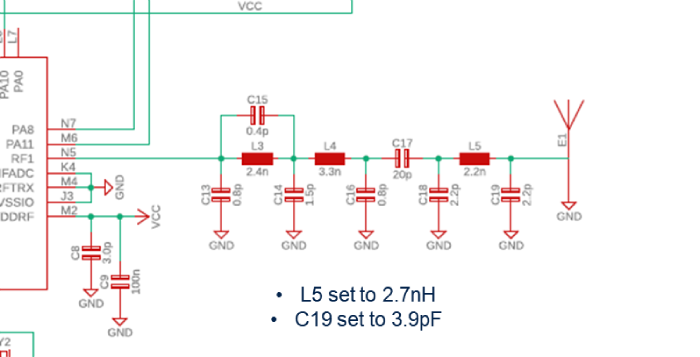

Work done:

The antenna was brought back to a better resonance on the wanted bandwidth by tuning the antenna-matching components.

Results:

Current consumption in the active phase is now back to expected values, which enabled the customer to increase his battery lifetime as anticipated.